A choice that is favorable to an individual may produce undesirable results for both the individual and society. This is the type of social dilemma that Associate Professor Ai Takeuchi focuses on in her research. By conducting analyses grounded in game theory and laboratory experiments, she explores mechanisms that induce cooperation in situations of social dilemma.

Are penalty systems effective in social dilemmas?

There are many situations in society where choices that are individually rational do not lead to outcomes that are desirable for society as a whole. In addition, when many people make self-serving decisions, the result is ultimately harmful not only to society but also to the individuals themselves. These kinds of situations are called social dilemmas, and environmental issues, for example, fall squarely into this category.

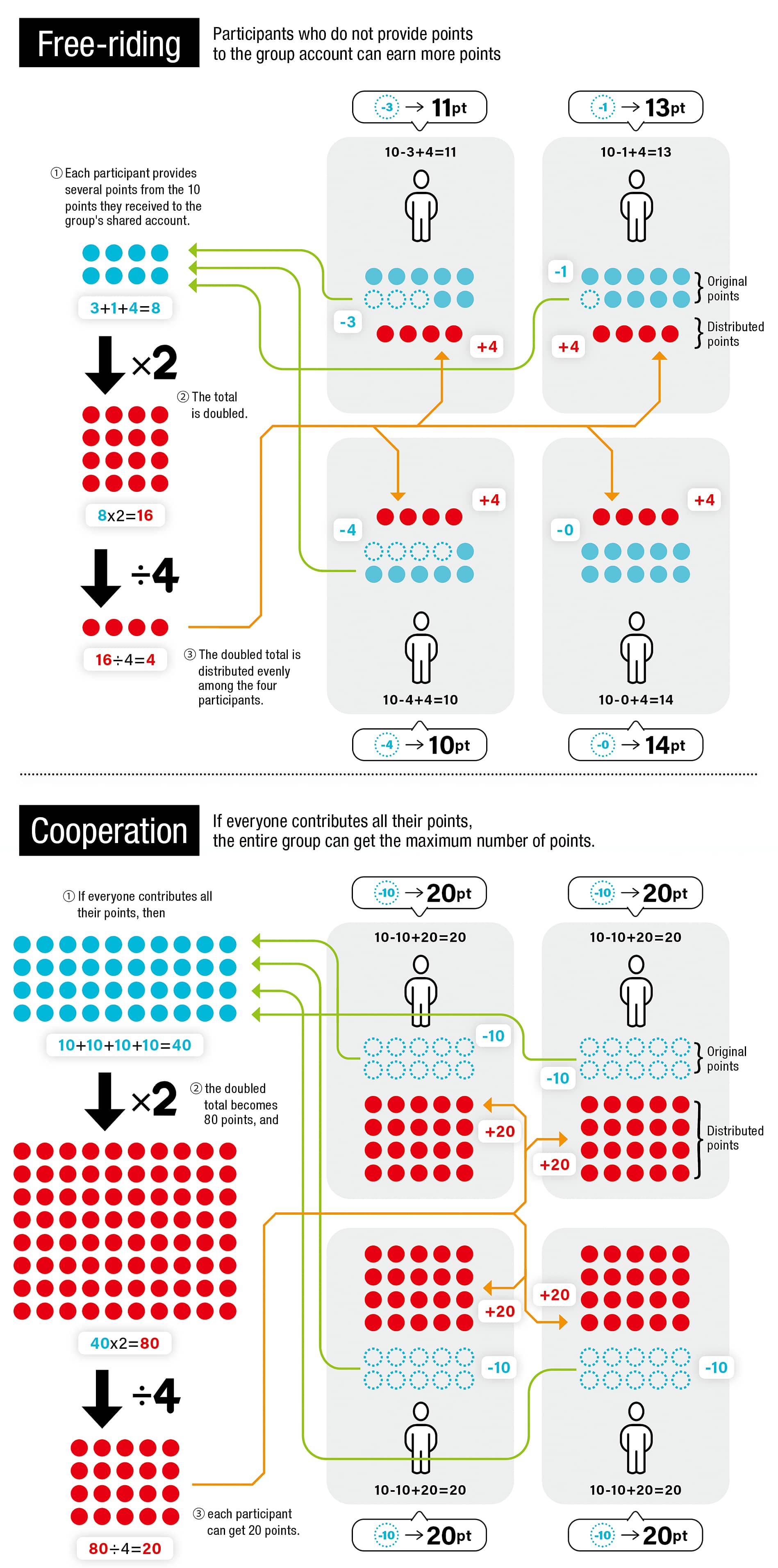

How, then, can cooperation be fostered in the midst of social dilemmas? Takeuchi investigates this question using methods from experimental economics. “In my research, I simulate decision-making situations that take the form of social dilemmas within the laboratory, and then analyze participants’ behavior through controlled experiments. One of the tools I often use for these experiments is public goods games,” says Takeuchi, who explains how one of these games works as follows (see diagram below).

Groups of four are formed, and each participant is given ten points. Each participant then has to decide how many of those ten points they will contribute to the group account. Any points they do not contribute remain their own, but the total points contributed to the group account are doubled. That doubled total is then divided equally among the four participants. This creates a dilemma: individuals who contribute nothing (free-riders) can sometimes come away with more points than those who cooperated; however, if everyone contributes all ten points, each participant will receive twenty points—more than they would gain if no one contributed anything. This raises the question of how to encourage the participants to contribute more in these kinds of situations.

“One possible way to encourage cooperation is punishment (or sanctions). Previous studies of public goods games have shown that peer sanctions can encourage cooperation, but the effect depends on the severity of the punishment. If penalties are too weak, they fail to increase cooperation. If they are too strong, however, the cost of punishment can outweigh the benefits of cooperation,” explains Takeuchi.

In a joint study, Takeuchi and her colleagues introduced a new twist: participants were assigned a contribution quota, and those who fell short of it were punished. The team tested and compared two different punishment systems. One was an absolute penalty system where everyone who provided fewer points than the quota was penalized. The other was a relative penalty system where only the participant with the least contribution among those who failed to meet the quota was penalized.

Takeuchi and her team first modeled these systems theoretically using game theory, then they conducted laboratory experiments to see whether the actual results matched their predictions.

“In theory, when punishment is severe, there should be no difference between the two systems, but when punishment is weak, the relative punishment system should be more effective at encouraging cooperation, leading to a higher overall point total (level of contribution). This is indeed what we observed in our experiments. However, at the punishment level that should, in theory, maximize contributions and gains, both systems unexpectedly saw an increase in the number of participants failing to meet the quotas. This observation contradicted the theory that cooperation can be sustained,” says Takeuchi, who thinks this might be due to “information about others’ behaviors.”

What caught the team’s attention was that when individuals deviated from the theoretical predictions, the points (gains) they earned were higher than those who did not deviate. “In other words, the gain appears to be higher for those who do not cooperate, even though in fact they themselves gain more by cooperating.” It is possible that the participants in the experiment saw others who were not cooperating, misinterpreted these facts as ‘higher gain,’ and chose not to cooperate.” These results suggest the extent to which information about others’ behavior is important in encouraging people to act cooperatively.

What kind of information is effective for encouraging teamwork and cooperation?

Two types of information raise cooperation rates

In her most recent research, Takeuchi is focusing on situations where people face multiple social dilemmas at the same time. She explains: “Take, for example, a disaster site. There may be several areas in need of volunteers, each with a maximum number of people they can accept. Here, two problems can arise: there may be some people who choose not to help at all (free-riders), and there may be coordination failures where it becomes difficult to efficiently allocate who should help out where.” So, what kind of information can effectively address these problems? Takeuchi and her team defined information on the maximum amount of required contributions (i.e. the number of people needed at each location) and real-time information on the contributions of others (i.e. how many people are cooperating where). Then, they modeled a public goods game with multiple (i.e. two) cooperation targets (contribution sites), each with a required contribution amount (upper limit), and used game theory and laboratory experiments to verify whether each piece of information can help overcome the problems of free-riding and coordination failure.

The results confirm that cooperation rates increase (i.e. coordination failures decrease) when both information about the contributions of others and information about the level of contribution required at each location are provided. On the other hand, they also found that when the upper limit for the required contribution was low, the number of free-riders increased and the cooperation rate dropped drastically. In their analysis, Takeuchi and her team note that this resembles concepts from social psychology such as the bystander effect and the diffusion of responsibility.

In Japan, where natural disasters occur frequently, encouraging people to cooperate in charitable activities such as volunteering and fundraising during disasters is an important issue. The findings of Takeuchi’s research provide valuable insights into how this kind of cooperation can be promoted.